I interviewed Beatrice K. Otto, an author and independent scholar best known for her award-winning book Fools Are Everywhere: The Court Jester Around the World, a cross-cultural study of jesters and fools in history. Her research draws on five years of research from sources in Europe, China, India, Africa, and the Americas to explore how these witty figures influenced courts and societies across the globe. You can visit her website to read more about fools and jesters here, and purchase her book here. Below is the transcript of our conversation, lightly edited for clarity.

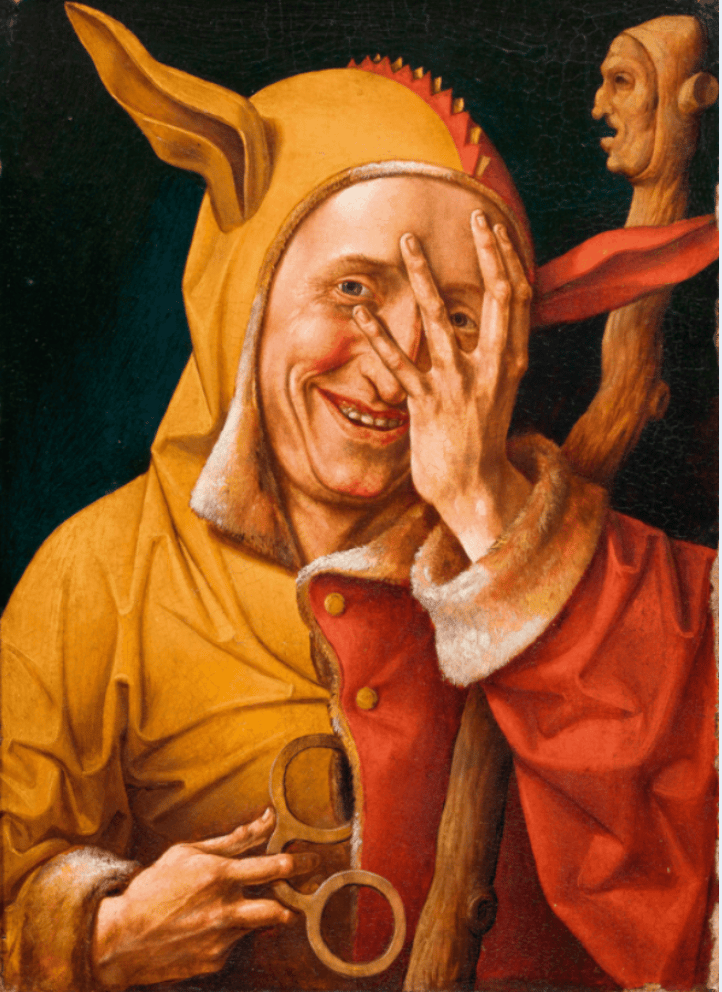

Painting of a jester (c. 1550), oil on wood, by the Master of 1537 (Frans Verbeeck?), private collection, previously on loan to the Musée départemental de Flandre in Cassel, whereabouts now unknown. Text description courtesy of Beatrice Otto.

How did you become interested in the history of jesters?

I was studying classical Chinese, and I came across some biographies of Chinese jesters written in first century B.C. And what struck me about them is they were exactly how we envisage a jester. And I think the archetype for Europeans or Westerners is Lear’s Fool. And it was exactly that kind of role. And I just found that amazing. Here you are in China, first century B.C. and you have jesters fulfilling what we would think of as a quintessentially European role with emperors. And that sort of sparked an interest. It ended up sort of snowballing and I pursued every lead I could find, wherever it took me. And I came to the conclusion this was pretty much a universal role in that it's not the product of a European culture or any particular culture, but it can crop up in quite a wide range of cultures.

I think it is shocking to people that China had jesters, because you think of this image of a very static oriental despot, that kind of image that you then have historians writing about. But [we have evidence] the jester said this, and the emperor burst out laughing, and the emperor gave him a reward. And it was completely outside our expectation of what a Chinese emperor would do.

Were jesters in other places too, besides historical Europe and China?

India as well. Even today, there are a lot of stories about Chinese and Indian jesters, also in Central Asia. I've come across references in the Middle East and in the Arabic world as well. Even the Aztec, I've come across references. What's interesting, wherever it's mentioned, it's not mentioned as being some distant exotic thing that you only expect to happen elsewhere. It is mentioned as a very natural phenomenon in that particular cultural context.

A depiction of jester Dongfang Shuo 東方朔 (c. 160 – c. 93 BCE) by 18th-19th century Japanese artist Torei Hijikata 土方稲嶺 (1741-1807). Shuo served the Han dynasty emperor Han Wudi 漢武帝 (r. 141-87 BCE) and accounts of his acting as a robustly outspoken, truth-telling jester…his willingness to speak out in even bold reprimand, and notes that the emperor always listened to what he had to say. Text description courtesy of Beatrice Otto.

Who was a jester?

They were from relatively humble backgrounds. There were some people from a more noble background who could take on that role, but by and large, they were from humble backgrounds. It was quite a sort of meritocratic, informal process. For your prime minister, [there] would be a more formal process, but [a jester] could be coming from a general pool of entertainers, jugglers, minstrels, musicians; quite a few of them had a musical element. So you could be a musician and then you've got a sharp tongue or a quick wit, and you sort of morph into the jester. Sometimes you even have people, a noble of the court traveling and then he'll encounter what you might term the village idiot or somebody in the village square who's goofing around and he'll say to the king, ‘I think I've found your next jester’.

Was it a full-time job?

Yeah, they were paid and it was full time. You never find things saying what their duties were, but they didn't have another job. You would just be the jester and you'd just kind of hang out. You might get involved in helping with court entertainments, but essentially it was about companionship and just being there. It was an interesting role. And then this whole advisory element, or the critical element also came into play because they were usually from a humble background, and they're kind of on the edge of the events, so they're not scrambling for power and position like the nobles may be. I think in that sense, a king or an emperor could relax a little bit and trust what he was hearing. There was less of a vested interest, and he's less of a threat. If he's from a humble background, he's less likely to use [his role] for power.

Were they usually men? Were there any women jesters at all?

There were female jesters in Europe, [less so] outside of Europe, I think. I recently read a paper about Persian jesters, and there were one or two female-named jesters mentioned. But in general, most of them are European. In China I never came across one at all. So in general, they're European.

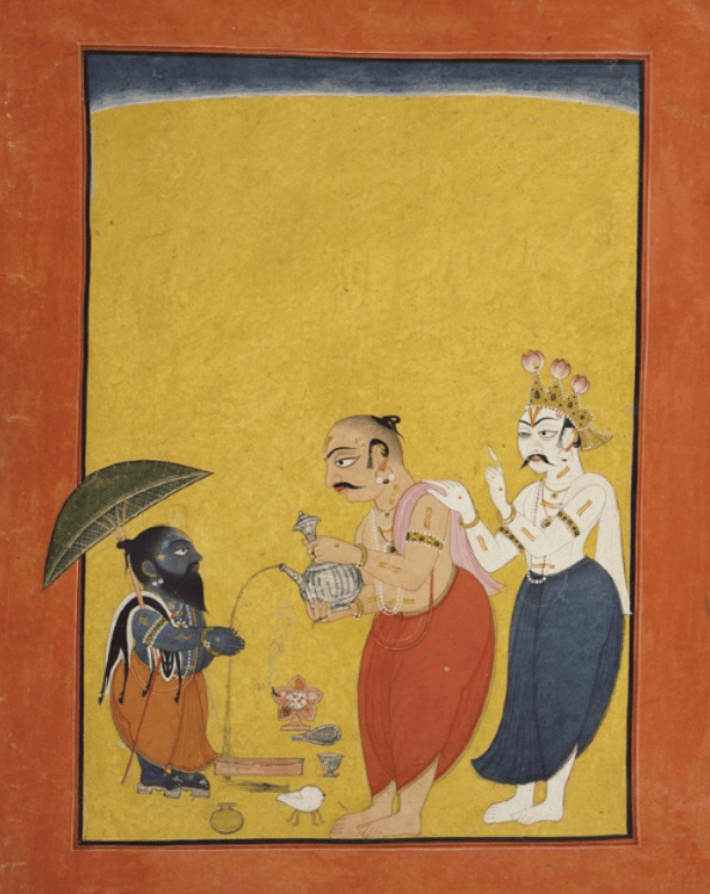

Another interesting element is, in many courts around the world, but particularly in Europe, you had a lot of dwarfs. Many jesters were dwarfs, including in China. I think partly because they have literally a different perspective on the world. So, it was quite common for jesters to be dwarfs. A lot of paintings in Europe of court jesters were dwarfs.

‘Vamana, the Dwarf Avatar of Vishnu’ (c. 1700-25), by unknown artist, opaque watercolour, gold, and silver-coloured paint on paper, page from a dispersed series of the Bhagavata Purana (Story of the Lord Vishnu); 125th Anniversary Acquisition, Alvin O. Bellak Collection, 2004, Philadelphia Museum of Art, public domain. Text description courtesy of Beatrice Otto.

Were they paid?

In Europe we have a fantastic record of things; the court account books can be terribly dry and boring. ‘This much was spent on this much firewood’. But in terms of jesters, it gives you really interesting insights, such as this much was allocated to the jester for ice in summer, in the heat of the summer in Spain. The clothes given to the jester, it's not cheap stuff. It was very nice. Sumptuous clothing, all kinds of gifts. In China, they give them bolts of silk as a reward for making them laugh. They were cared for…People sometimes think they were just sleeping rough with the Spaniards, just kind of sleeping on the floor, a bit of straw, but they were really quite well looked after.

The clothes given to the jester, it's not cheap stuff. It was very nice. Sumptuous clothing, all kinds of gifts. In China, they would give them bolts of silk as a reward for making them laugh. They were cared for.

Were there any unusual jesters?

In Europe, especially if they had some sort of mental aberration, that was another candidate for being a jester, and they would have a carer—somebody whose job it was to look out for them and look after them.

The idea of having a dwarf…or a hunchback as a jester [was] quite natural. It's not unusual, but this whole mental difference or diversity is really more of a European thing, and it's quite interesting. It can be sometimes somebody from the village; a village idiot. The village fool would be taken care of by the king.

Was there one jester for an emperor or king, or were there multiple?

It can be multiple. There was usually one or two key ones at any one time. It was mostly a one-on-one relationship. But it might be that the king would have a jester and the princess would have her own jester or court dwarf or a court jester for herself. So you'd have more than one in the court. But usually there was one predominant one, and sometimes there would sort of be passed on to the next king. There's one jester who was jester to Henry VIII and when Henry VIII died, he went to Mary and then he went to Elizabeth I. So they just sort of get passed on.

In China, there would be more than one. They still had these famous ones that were named and known, and had a close one-to-one relationship. But they also had jesters like semi-actors that would get together and say, ‘we need to criticize the emperor on his policy, on taxation or whatever. His policy is not good for people.’ And so they'd cook up a little skit between them and they'd act out a skit. And it was a way of advising the emperor. And the emperor often would respond to it and said, ‘okay, okay, I get it.’ It might be a criticism of nepotism in the court that the emperor is appointing all his sons and cousins and so on, so they could use this as a way to present a critique effectively.

They also had jesters like semi-actors that would get together and say, ‘we need to criticize the emperor on his policy, on taxation or whatever. His policy is not good for people.’ And so they'd cook up a little skit between them and they'd act out a skit. And it was a way of advising the emperor. And the emperor often would respond to it and said, ‘okay, okay, I get it.’ They could use this as a way to present a critique effectively.

Did they wear the typical outfits that we typically think of?

The uniform we all recognize was European. Outside of Europe, there's no sign that they wore any particular clothing. And in Europe, there's a lot of debate as to whether that clothing was more a literary device or an artistic device [rather than real clothing they wore]. It was certainly very visible in many forms of art. My feeling after reading through whatever I could find on it is that in general, they didn't wear the cap and bells and that kind of multicolored party cloth, certainly in medieval times. And yet that comes up in art, but I don't think it's what they wore from day to day. We have real portraits from Spain where they did half a dozen paintings of real historical jesters, and there are many others. And they're wearing what other people wore in the court. They're wearing the standard clothing of the period. So in many cases, it would be a doublet and hose for a 16th Century jester.

In Europe, there's a lot of debate as to whether their clothing was more an artistic device [rather than the real clothing they wore]. My feeling after reading through is that they didn't wear the cap and bells and multicolored party cloth. We have real portraits from Spain where they did half a dozen paintings of real historical jesters, and they're wearing the standard clothing of the period.

'The Fool: young boy in the costume of folly’ by Philippe Mercier (1689-1760), an artist active in England. Oil on canvas; private collection. Source: Der Narr.Text description courtesy of Beatrice Otto.

Do you think jesters came from the first human civilization?

My feeling is that it just popped up sort of spontaneously in different cultures. There are hints, very tentative hints of a jester role in Mesopotamia tentatively, then obviously China. The idea of the jester coming to Europe through China or India, I don't think so. Within Europe, you have kind of jokes or stories that travel, so you have real jesters and you have real stories about them. And then you get kind of generic stories that get pegged onto the jester, and then they get attributed to different jesters and you say, well, wait a minute. This is the exact same story being attributed to multiple jesters around Europe. That's a little bit of somebody collecting things into a jester book.

What kind of jokes were they making?

What I've come across, it's not like a standard pattern of jokes from a joke book. It's rather making a mockery of the situation in front of them. It can be mocking somebody in the court or just criticizing in a funny way. So it's not like you can gather up their jokes and put them together and say you can use this in your performance. It doesn't work like that. It's more a direct interaction between the jester and the people or person in power to influence or change behavior or just entertain them. It'd be hard to come up with a joke book from jesters.

Where were they performing?

They'd just be with the king or the princess, and they might be sitting next to them or near them and it is a very natural sort of human connection, which is interesting. We're talking about courts that were for the most part very formal. They had formal structures, limited access to the head honcho, and then you've got this guy or occasionally woman who could just have access and just walk around and stick their nose into things if they felt like it.

Were they ever in trouble or even killed for saying something?

They could be beaten or kicked out or exiled from the court, but being killed is unusual. But it did happen. I've come across a couple of examples in China, and in one case, the emperor, afterwards really regretted what he'd done because the jester was joking with him to criticize him for drinking too much and not paying attention to the affairs of state. And maybe he was drunk at the time, and he lashed out and killed the jester. And then afterwards he said he was only trying to help me, so he regretted having him killed.

And then there's another famous one of a very lively Chinese jester where the emperor was insulted by the jester, so the joke fell flat. The jester made a pun on the emperor's name that was insulting. The emperor was outraged and apparently took a bow and arrow and was about to shoot him, and he talked his way out of it. You've got to have an unbelievable presence of mind and nerve to sort of stay cool and say, ‘okay, I better crack a good joke now, otherwise I'm dead.’ So one or two Chinese jesters were killed, but by and large, no.

Many rulers in the past had the say over life and death, and so they could have you beaten or killed or whatever. And yet there was a widespread recognition that the jester has this license to criticize and speak truly, and an appreciation of that. So you've got a very formal structure where everything's controlled, and then you allow this symbol of free range chaos, even if sometimes then you've got a bad day with your court, and he says something and he annoys you and you slap him across the face. But the underlying appreciation of that role and the freedom was kind of amazing.

Many rulers in the past had the say over life and death, and so they could have you beaten or killed. And yet there was a widespread recognition that the jester has this license to criticize and speak truly. You’ve got a very formal structure where everything's controlled, and then you allow this symbol of free range chaos.

When did the traditional jester role disappear?

In Europe, I'd say it was fading in the 17th–18th century, you still had one or two, not in the main court, maybe in a noble household, you might have one into the 18th–19th century, but basically fading out. Then Russia went on a little bit longer. China probably similar, 18th, 19th century. The references dry up thinking about why, and I don't have a clear answer. In Europe from the medieval time through the Renaissance, you had a sort you had a crazy interest in jesters. So fools and jesters permeate art and literature. There was a kind of obsession with them, and it may just be that just petered out naturally.

It could be partly the rise of the theater. As the theater became a more prominent form of entertainment, that sort of took over from that role. I mentioned that you had those groups of Chinese jesters who'd put on a little skit. That was in some ways a kind of prototype drama in China, and then the Chinese theater took off. So that may be another reason, and perhaps another reason in Europe was to do the enlightenment where you put more emphasis on rationality and reason, and that doesn't quite fit with having a sort of half mad, chaotic figure laughing at you when you think you can reason everything out. So very tentative answers to that. It's a difficult question.

Were there any other differences between jesters across countries?

The [mentally ill jester] being much more a European phenomenon. Another is the amount of artwork in Europe depicting fools from medieval times, certainly through the Renaissance. It's an explosion of art related depictions of them, and you barely have that elsewhere. It is very hard to find in China. I've been looking into pottery, figurines, terracotta, figurines of entertainers to try to get an idea of what the jesters may have looked like, but it's nothing like the same. This sort of craze for fools and folly happened in Europe.

Is there anything else surprising that people might find about jesters?

I think the extent to which they could speak truth to power. Because some terrible monarchs, despots and tyrants had jesters, and they were allowed to speak. And in a society where you could have your head chopped off for nothing, I think it's astounding the skill of the jester in general—to read the situation, read the psychology, and figure out how best to approach a tentative subject. In Europe, the courtiers would ask the jester to help them get something through that may not be popular. And the same in China. There are stories of jesters interceding on behalf of courtier or others and succeeding in whatever it is, getting better conditions or mercy or whatever it is that they needed help with.

It's astounding the skill of the jester—to read the situation, read the psychology, and figure out how best to approach a tentative subject. In Europe, the courtiers would ask the jester to help them get something through that may not be popular. There are stories of jesters in China interceding on behalf of courtiers and succeeding in getting better conditions or mercy or whatever it is that they needed help with.

Do you see any similarities to historical jesters and modern comedy?

For me, two things have kind of inherited the jester's role: standup comedians and cartoonists. They have a capacity to criticize using humor. If I were a leader, I would want to see the key cartoons every day in my briefing pack. I'd want to see what key comedians are saying about whatever it is, I doubt the White House or 10 Downing Street has it in their briefs, cartoons and comedians, skits on them or whatever. But it would seem to me a very good source of intelligence as to what's really going on and how people really feel. And that role of the jester, not just being a lightning rod, but also keeping the king connected to the ordinary people and being in touch, perhaps being one himself, being from a humble background, that role is still played by comedians and cartoonists. The only difference I'd say is that the jester literally had the ear of the emperor or the king, and maybe the comedian. I don’t know if they have the direct [access].

But you hope [leaders] are paying attention, because the other thing that the comedians do is they distill the issues, they make them very clear and they get through all the complexity. I mean, some things like the subprime loan crisis, when that happened, I couldn't understand what it was about. And then I found a sketch by two English comedians, which had me laughing my head off, and I thought, okay, now I understand it. Their way of portraying it was hilarious, but it was also really insightful. We need those people more than ever.

'Cardinal Granvelle's Dwarf with a Dog' (c. 1549-60), Antonis Mor (1519-75) - Louvre Museum, Paris, public domain; photo credit: Sailko. Text description courtesy of Beatrice Otto.